Traces of the Tibetan Year of the Rat

by Woeser

Each year since, on this day of memories, it looked as if nothing had happened;

But that year, the crisis flared: he rushed out, she kept screaming,

And many nameless ones long hid in shadow

Threw off their lifelike masks of satisfaction.

A moment turned eternal: blotted out, they became secrets of state.

At dawn I stealthily push open my door.

In all I meet today, will there be any traces of the Year of the Rat?

I think I’ll manage to see what I’m not supposed to see.

Along my way are those repairing shoes, making keys, setting out to mine ore or build dams:

Hardworking migrants on their daily round—

Been up for hours, like the Chinese steamed buns awaiting hungry prospectors.

At every intersection stand extra cops (the special ones in black uniforms)

Back to back, girded with shinguards, gripping shields and weapons;

And at countless observation posts you’re surrounded by spies and surveillance cameras,

For to one side there are always a few men smoking and casting glances,

ready to tail anyone who doesn’t follow the script.

Two plastic mannequins propped in a shop’s doorway catch my eye.

They’re scantily clad in cheap undershirts of gaudy red and green,

With a cord round their necks, as if two poor souls had hanged themselves on the security grille.

Did the shopkeeper think anyone would make off with them?

At Dzongyab Lukhang, often I linger

To drink in such news and gossip as is still shared there in the mother tongue.

But today the scene makes me shut my eyes tight:

In the background, a ray of light falls precisely on the Potala and catches,

Jabbed into the top of it, a red flag with five stars

—The murder weapon, revealed.

That sunbeam’s like the light that shines upon the bardo,

Except our hope’s not in the life to come, but in the lives beyond counting that are gone.

I reach a grove of willows that was cut down and is now growing back,

And the long strand of prayer-flags which dipped to the water now flutters anew;

But this pond must be the lake as it was of old, rimmed with green fields,

And holding but a few coracles paddled back and forth

By young men and women arrayed in silks and jewels, so fine,

As if they’d come back from the land of the dead.

At its center stands a small temple like the words of a song . . .

Dreamlike scenes, as from a mural—but one bearing the marks of a knife.

Is it possible all the wounds have been healed on command?

Can every imprint have been carefully rubbed smooth?

In this disquiet can we live the way we used to, as if nothing were wrong?

Darkness falls swiftly and gives me no time to prepare for it.

A column of armored personnel carriers gets under way like muffled thunder,

And a babel of regional Chinese accents, punctuated by police whistles, sets me on edge.

They have the air of those who always win. Tomorrow they will be transformed—

The older ones into seniors with gravitas (they have no shame!), and the young ones into jaded tourists.

Dogs join the din, barking wildly.

Without looking, I can feel the Potala is there, a stone’s throw away.

It keeps silent in its loss, yet refuses in its silence to accept the loss.

I remember the flames of a fire first kindled at Ngaba—

No, those were not flames but protector deities, one hundred thirty-five of them,

And they are arising still.

I retrieve a fallen tear and place it gently in the basket on the altar.

Translator’s Note:

In the years since completion of a high-altitude rail link to Lhasa in 2006, the city has experienced an influx of Han Chinese tradesmen and workers, in addition to the heavy police and military presence which is predominantly Han.

The Year of the Earth Rat, according to the Tibetan and Chinese calendars, was 2008. That year, a movement of protest and resistance (mostly non-violent, with the exception of the March 14 riot in Lhasa) spread throughout the Tibetan areas of the PRC and was forcibly suppressed.

Dzongyab Lukhang is a park in Lhasa, north of the Potala Palace that was once the home of the Dalai Lama.

The bardo, in Tibetan Buddhism, is a state through which a person passes between one incarnation and the next, that is, between death and re-birth.

Ngaba is a county in the southern part of the traditional Tibetan zone called Amdo, in Sichuan Province. On February 27, 2009, a young monk named Tapey set himself on fire there after authorities cancelled prayers at Kirti Monastery. In the years since then, more than 130 Tibetans have self-immolated in protest. Woeser’s analysis of this phenomenon has been published in France as Immolations au Tibet: La Honte du Monde (Indigène éditions, 2013: transl. Dekyid) and in the United States as Tibet on Fire: Self-Immolations Against Chinese Rule (Verso, 2016: transl. Kevin Carrico).

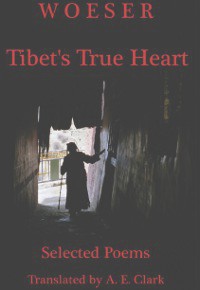

Woeser contributed this poem to the anthology Liberation: New Works on Freedom from Internationally Renowned Poets (Beacon Press 2015; ed. Mark Ludwig), where this translation first appeared.