An Education in Cruelty

by Ye Fu

Is human cruelty an instinct of our animal nature or a genetic trait? Is it a dysfunction forced on us by a particular kind of society or does it arise from an individual’s education and upbringing? Can we adapt Tolstoy’s celebrated dictum to say that all good people are basically alike, but every cruel person is cruel in his own way?

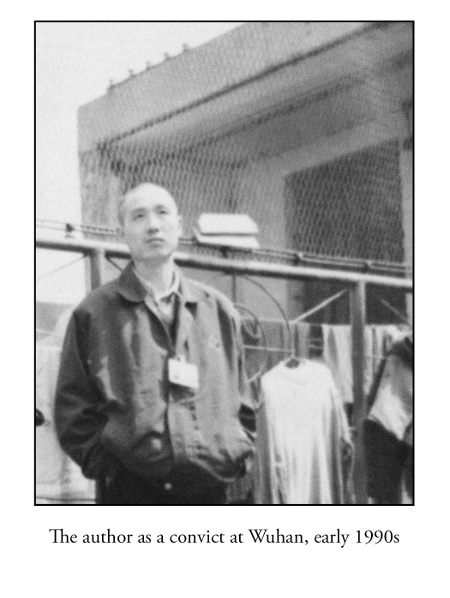

Long ago while I was incarcerated, my mother wrote to tell me that my daughter (who at that time was not quite six years old and didn’t know her father) had undergone a troubling personality change. She would take a kettleful of boiling water, for example, and slowly pour it into the fishtank and watch the fish struggle desperately with no way to escape, till at last they were scalded to death. My mother was afraid the child’s play revealed a cruel streak. The news shocked me, but I realized on some level that almost all human cruelty partakes of the nature of a game, and in a great many games there is an implicit cruelty.

I didn’t hold it against my daughter. One could attribute her behavior to immaturity, the lack of a father-figure, and the fact she had not yet received any precepts about the safeguarding of life—precepts more or less religious in origin, but typical of civilized society. She was still in a state of primitive barbarism that recapitulated the early history of the human race. But then I thought back to the rough childhood I had endured in a remote small town, and it dawned on me that by growing up in this country I had received a whole education in cruelty. Considering that adults still play (or at least tolerate) all kinds of sick, cruel games, I’d be ashamed to judge a child harshly.

That famous period of ten years commenced when I was four years old1 and found me in the state of nature. There was at that time no regular kindergarten or preschool instruction, and naturally there was a complete lack of educational pastimes. The first game I learned from the older boys in the village was to catch a toad out in the fields and make a little kiln of mud, inside which we’d spread a layer of quicklime. We’d put the toad inside and seal up the kiln with thin streaks of clay, leaving a little hole on top through which to pour cold water. On contact with water, the quicklime was energized and generated a great deal of heat, and as the steam curled up, there rang out a croaking cry of tortured pain, first very strong and then fading away. When the steam and the noise were both finished, we’d rake open the mud kiln to find that the toad’s ugly skin had peeled off, exposing the trunk of its body, translucent and glowing like the flesh of a newborn child; for in death the toad revealed a beauty of extreme purity.

Who had invented so cruel a pastime? The children must have come to it by imitation, but what exactly were they imitating?

For years I have had a recurring dream in which I am standing naked under the blue sky of late autumn, trying to soak up enough sunlight to survive the winter—for the winter is going to be exceptionally cold. The rays of the setting sun slant over the high wall behind me, casting an enlarged shadow of me on the wall in front. The shadow of the electrified wires just happens to cross at my neck, making the silhouette of my head look like a wild fruit overripe amid a tangle of withered vines.

This made me realize that if immersed in a savage reality, the heart becomes inured to cruelty: it has to. This scene, which I had actually experienced, was so frightening at the time that it was later fashioned into the image of a recurring dream during a long spell of ordinary life. I would like to identify the moment when I began taking cruelty as a matter of course. When did we start to accept malice and violence as a part of normal life, excusable and unchecked by any law?

I was six . . . yes, I was six years old and in the first grade. Early autumn, 1968. When school let out, the students were assembled and a vigorous teacher took apart a big broom and gave each of us children one of the bamboo stems. Then we lined up and headed off to administer a beating to a thief. When our troop of scouts came marching down the street, the townsfolk who had surrounded the thief raised a jolly cheer. The thief had been made to stand on a cement culvert pipe. His shirt was tattered and his trouser-legs had been rolled up over his knees as if he had just come in from the paddies, and he was shod in straw sandals. These particulars are etched in my memory because our height reached just about to the man’s ankles. The grown-ups were loudly urging us on, “Beat him! Beat him!” and thus the small town’s Carnival of the Thief got underway.

We schoolchildren from the village ranged in age from six to sixteen and, giddy at being for the first time encouraged by adults to beat up another adult, we didn’t hold back. Lashed like a top by countless bamboo rods, that middle-aged thief began to hop and prance along the pipe in a dance that never let up. There was no escape. To whichever side he was driven, a dense screaming throng was waiting to whip him. I distinctly remember the coarse skin of his calves, still a little muddy, slowly turning from red to purple, then gradually swelling and turning white and translucent like a turnip. He kept uttering little cries and desperately flailing his hands and feet. The drops of his sweat fell like rain and there shone from his eyes the cold light of death. I swung at him a few times. Then, frightened, I held back, but the grown-ups and the other children were still engrossed in the delightful sport they had devised. Finally I noticed that he had grown so hoarse that his mouth opened and shut soundlessly like a fish and his body was shaking like a kite off-kilter, and when one more blow came, the blow that was one too many, he fell with a crash . . .

When first summoned round him, we had learned from the grown-ups’ execrations that he had been arrested for trying to pilfer three feet of cloth from a tailor’s shop. He was a peasant come in from the country to attend the fair. Remorse haunted me later. I kept thinking that life had prepared the same winter for us both; in fact his kids, about my age, wore rags and he had no money to make them warmer. And on this day he had spied those fatal three feet of cloth. Each time I recall the scene, the pain reaches a bit deeper. Having written thus far, I find tears running down my face and I realize that this was the beginning of my education in cruelty.

It’s often hard to identify the moral quality that makes some hurtful acts cruel. If in a room full of mosquitoes we were to shut the doors and windows and light a coil of insecticide in order to exterminate the pests, no one would condemn us. What about mice? Well, they spread disease and steal food, so they too deserve to be exterminated. As for the means employed to exterminate them, people don’t usually inquire too closely.

When I was about ten, my mother sent me to the coal mine because my father was being punished in all sorts of ways after being “knocked down.” It had proven too much for one of his colleagues who had already committed suicide. Mother was worried and sent me to keep him company, thus introducing me to the real life of the working class. There were many rats in the mine then, and the men who constantly risked death in the pit had nothing in the way of entertainment, so in their moments of free time they tried exterminating the rats for fun. They used all their wiles to capture a rat alive. Then they’d stuff raw soybeans into its rectum and sew up the anus. The soybeans would expand inside the rat’s body and drive it mad with pain; then they’d let it go and watch it run around in a frenzy, careening back to its home where it bit and scratched at its own kind, creating a rousing spectacle of mutual annihilation: this trick was more devastating than any poison. Or they would tie a wad of cotton soaked in gasoline to a rat’s tail and release it after setting the cotton aflame, and then watch with pleasure as the little fireball ran around crazily. These scenes frightened me. Nothing but disgust and hatred made them torture rats so: was this the human race’s idea of justice?

And what of how humans massacre each other? The Nazis’ hatred for the Jews, and the genocide they perpetrated, are too well-known to need recounting here. The hatred we once harbored for what was called the exploiting class seems practically on the same level. In my part of the country there was major landholder named Li Gaiwu; in the era of land reform he was crammed into a cage by angry peasants who then propped him over a fire and roasted him alive. Such a drawn-out, hideous death: none of us has even an inkling of the pain. If we review our penal history with its “death by a thousand cuts” and violent forms of sterilization and other such punishments, it is hard to believe we are a people under the guidance of reason.

A lesson taught us from our earliest years was that “Kindness to the enemy is cruelty to the People,” and this political ethic has always guided our social life. A maxim which Party members consider the Golden Rule demands that we treat comrades with the warmth of springtime, but to the enemy we must be like the autumn wind that blows away dead leaves without mercy. We recognize empathy as a basic element of human nature; the Buddha said that only with compassion can living creatures exist. To be without empathy, to be ruthless, means we need only take a political stand and can dispense with fundamental human considerations and instinctive sympathies. When dealing with outsiders (i.e., enemies), we may go to any length and take any measures to punish them.

In the natural order, it’s hard to distinguish between noxious insects and those that do some good. How accurately then are we likely to differentiate between enemies and friends, when all are of our own kind? The final decision will inevitably be based on power. When the highest authorities declared that sparrows were pests, these innocent creatures had to be exterminated by the entire people acting in concert. For these little birds, the sky suddenly shrank; they were massacred; they fell in droves, dead from exhaustion as they struggled to flee the country. If birds fare thus, how can men endure? When we calmly look back on the whole twentieth century and consider all the people we called enemies and the animals we called pests, how many of them look entirely evil or destructive from today’s vantage point? Those poor teachers, or fellow-soldiers, or relatives or neighbors might, depending on the unfathomably mutable dispositions of the supreme authorities, flourish at morn to be cut down at night. Is there anyone who has not tasted this cruelty?

In 1976 I was a student in early middle school in my small town. That year there was a great deal of grief and laughter in our country, emotions that took many forms and were seldom openly expressed.2 Historians will see this as a year of transition. That winter, we students were taken as a group to participate in a public trial and sentencing at which a counterrevolutionary named Yang Wensheng was to be shot. From what we could make out of the not-very-clear verdict, this was a man so bad that even his death would scarcely suffice to appease the People’s wrath. His crime was that when high authorities had arrested the Gang of Four, he insisted that—based on the principles and examples of historical fiction—this had been a palace coup. He was constantly making speeches and pasting up large-character posters opposing the Central Government under Hua Guofeng. He called on people to guard the heritage of Mao while resolutely opposing the return of the capitalist-roader.3 Prior to this, he had been well-known in town as part of the extremist faction of the Red Guard and had, to be sure, persecuted some of the local cadres.

In those days, many of the ancient formalities were still observed while a prisoner awaited execution. The man was tightly bound with ropes and once the sentence had been read aloud, they thrust down the back of his shirt a sharp stick on which the name of his crime had been written. I saw him grimace with pain then, but he was bound so tight he couldn’t cry out. A few of us bold kids hopped on our bicycles and followed the prison van to the undeveloped land outside the town. There he was lifted down out of the van and kicked to his knees on the frozen ground. From less than a meter away, the executioner deftly fired at the man’s back and he pitched forward. Though his crumpled body shuddered a few times, he soon became still as the echo of the shot reverberated off the surrounding hills. A throng of all ages, male and female, had gathered to watch. In a society rife with tedium, an execution served much the same function as a wedding banquet: the man’s death provided a little zest for the masses. A grown-up went and turned over the body and loosened the clothes, and we were startled to see blood still flowing from the bullet-hole on the left side of his chest, as the last of his body’s warmth dispersed upon the wintry earth.

Thus was a life disposed of. Some time before, in the north a woman named Zhang Zhixin had been put to death in an even more brutal fashion.4 These two people were charged with the same crime, though in substance their actions were diametrically opposite. We could say that Zhang died for her wisdom and clear vision, while Yang died for his folly and stubbornness. What got both of them in trouble was that at that stage of history each was a person who stuck to his convictions and expressed them; how the world later gauged the validity of their beliefs is irrelevant. They were punished as criminals for nothing but their expressed opinions: they led no rebellion, committed no murders, burned no buildings. Every civilized country writes freedom of speech into its constitution as the citizens’ right. Yet for attempting to exercise this simple right, Zhang became a tragic hero and Yang remains forever a fool.

As we wander through this world, the fleeting pleasures of the senses make us cling to life, and the religious ideal of self-sacrifice presupposes heroic virtue. To survive, we must vie with other species for the means of life and if an instinctive animosity arises from this situation, it is hard to fault men for it. But when there is a life-and-death struggle of one man against another, or of tribe against tribe and nation against nation, and we must plot against one another and fight at close quarters: what moral criteria are laid down for human nature then? Can’t some principle always be found, such as individualism, nationalism, or patriotism, that will let us bend the rules and justify our violence?

When I ask these questions about the history of individuals, or the background of my relatives and friends, or the stories (both factual and imagined) of our people, I usually am left unsure what moral standards should be applied. The common people worship Heaven and Earth, and this teaches them reverence. The gentleman stays far from the kitchen and thus cultivates compunction.5 Reverence leads to awe, and compunction leads to love. Now if everyone were imbued with awe and love, perhaps there would be no need for religion, and we could still manage to live saintly lives. The difficulty comes when you dwell in an atheistic country where constant propaganda has exalted scientific fundamentalism into an overarching value, and where revolution and violent rebellion (such as led by Li Zicheng and Hong Xiuquan6 are the stuff of heroic legends. Is it possible to feel any awe under these circumstances? Can all the laws in the world check the malice latent in our nature, especially since it has been repeatedly encouraged and sanctioned?

In the perilous year 1949 my father, the son of a small landholder, sought safety by joining the new government. Calamities befell his family during land reform, but he became a hero—in another county—in the fight to suppress the ‘bandits.’ My father always tried to avoid discussing his past, rather as a bitter old man who had failed in life would fear encountering a woman he had loved in his youth, but I was able to piece together his story from the recollections of some who had known him back then. In that cruel time, he had to be particularly ruthless, since otherwise his loyalty would have been doubted on account of his background. When I think how he trapped and killed those fierce brave men of the highlands and signed death-warrants for landlords who had worked hard (like his own father) for everything they had, I am sure that this was not how he wanted to act. He was not stupid. He couldn’t have thought he was being fair, but he knew that if he revealed even a hint of human kindness, it would give others a reason to mark him for liquidation. It was like the organized-crime families in which junior mobsters must commit a murder as soon as they are recruited, to give proof of their staunchness. He had no choice.

After the Uprising of the Three Townships had been quelled,7 his pacification squad took about a dozen prisoners. From the county seat came orders to bring them into town, but my father had only two armed men with him. With their hands tied behind their backs, the bandits were marched toward the city, but they dragged their feet enough that nightfall found all of them still in a desolate part of the country. It was a dangerous situation. My father’s two subordinates suggested killing the prisoners and reporting they’d been shot while trying to escape. He was in charge; it was his call. For his men’s safety, he consented. The prisoners’ bonds were untied and they were told to run for it and take their chances. The three militiamen opened fire on the scattering fugitives in the moonlight, and hardly any managed to get away alive.

This was the cruelty that the revolution required. Long before, our Leader had used a series of parallel sentences to explain for us exactly what is meant by revolution: “an act of violence.”8 In our childhood, this startling passage was popularized as a song whose terrifying refrain echoed through the land. To its melody, kids gracefully brandished belts (and whipped their classmates who came from bad class backgrounds), forced their teachers to eat excrement, raided homes and pillaged them, and hounded innumerable innocents to death. I reckon that few in my generation were squeamish at the sight of blood, because we had seen so much of it. We had grown accustomed to all life’s cruelty and nothing shocked us anymore.

Apart from cases in which people are forced to be cruel, I am often puzzled whether cruelty stems from ignorance or hatred. Or could there be other causes than these two? After reading the letter from my mother, I remembered something that happened when my daughter was even younger and we lived together for intervals. She was a little more than one year old, still quite skittish in the presence of unfamiliar faces. Though her father, I was much like a transient visitor, and her tantrums left me at a loss. The best I could think to do was to carry her in my arms to the fishtank. It worked: the swaying, glittering fish caught her attention and she stopped crying. At first her tearful eyes tracked the soundless dance of the fish, and then when the fish tired and stopped moving, she reached out her little hand to slap the glass and stir them up. Startled, they broke in all directions and bumped into the glass as they fled. Only after some time did peace return. Then she’d bang the glass again, and once more the fish would flit around wildly. Eventually my daughter smiled through her tears. Perhaps she realized her power to tease these magical little elfin creatures and was pleased with herself.

When the game staled through repetition, she required more stimulation and ordered me to hold her closer to the tank. Then, to my surprise, she reached into the water to grab at the flustered fish. She was brazen about it and seemed perfectly confident that these small weak animals could do her no harm. What if they had been scorpions? What makes a child know instinctively whether it is safe or dangerous to tease a particular kind of animal? Do we have an innate ability to infer from the aesthetics of a creature’s form whether it is innocuous? The fish could not long evade her grasp, and when she’d got one, its panicked wriggling startled her and she threw it on the floor, where it flopped about like a mechanical toy before lying still. She burst into laughter.

Thus I realized that like me, my daughter was fond of fish. But her love expressed itself by tormenting the object of her love. This amorous baiting, as well as the full-blown cruelty to which it can lead, is often seen between grown-up lovers. Milan Kundera says in one of his novels, “They loved each other, but each put the other through Hell.”9 Cruelty that arises from attraction or love may be hard to understand, but it is all around us. My provisional term for it is ‘affectionate cruelty.’

From its origin to its dying-out in the life of our society, the term “rectification of styles” has a history spanning no more than half a century.10 Yet this term—not, on the face of it, a harsh one—laid waste the spirit of our people and to this day one can discern the scars it left behind.

For my generation the fear wrought by this term, a terror from which there was no escape, started in elementary school. At that time I had no inkling where the term came from; I didn’t know it had been invented at Yan’an and could make our parents’ generation blanch with fear. But when the term came back and repeatedly invaded our childhood, it inspired a dread which lingers with me to this day.

I don’t know how those who crafted this country’s educational system could have wanted to introduce the cruel ways of adult factional strife into the lives of inexperienced children. But I know that each semester, I quailed in anticipation of the Rectification campaign. Directed at children, it employed the same kinds of threats and blandishments as the adult version and taught a host of naturally kind and honest children how to denounce each other secretly. Although the substance of those accusations now sounds absurd—indeed, ridiculous—the seed of malice was being sown in our young hearts. When you saw a trusted friend step forward to denounce you, righteously, for some childish transgression that you had committed with him, you could not help feeling that human affairs and human nature were treacherous. In the train of betrayal and denunciation always came criticism and mockery, as every child lost all sense of decorum in an orgy of backbiting. Children’s innate sense of dignity and sincerity crumbled, to be replaced by a grown-up cunning and the skill to make others take the blame. I can still remember a girl from middle school, a lovely and gentle girl with a thick dark braid. Perhaps because her parents came from the provincial capital, she was a bit more mature in mind and feeling than the rest of us. In the course of one campaign for the Rectification of Styles, a classmate who was her closest girlfriend turned on her and reported hearing her say that she loved to look into the limpid eyes of a certain boy and often dreamed about him. The informer announced this in a tone of the strictest propriety, and the whole room rocked with laughter. Stunned, the innocent girl turned very pale, and then her face and ears flushed crimson and she ducked her head under her desk and cried in anguish. She wept in despair like a widow who has been caught in the act of adultery, and it made me and my peers, all equally confused in our teenage crushes, shiver with fear. A scarlet letter of shame was etched into the heart of a thirteen-year-old girl. She could not possibly remain in that school. Her family pulled her out and sent her to live with relatives in Wuhan, and later she was married off at an early age and became a housewife who sold snacks at a counter. After seeing how quickly a beauty and her youthful innocence were trashed, who could still put any trust in childhood friendship?

Informing, denunciation, betrayal, even entrapment: these defined the ethos of my world from childhood on, and there was no defense against them. What kind of a motherland would wish her children, at what ought to be a tender age, to learn such ruthless arts of survival? In today’s society I sense insecurity and constant danger everywhere, and most of it is rooted in the atmosphere of conspiracy and treachery that was fostered in our education.

What clings to all my memories of the time before 1976 is the smell of blood. I remember, when I was about eight, passing through the courtyard of the District Office at Wangying Town as dusk fell. Suddenly I saw some townsmen tie a peasant’s hands behind his back and hang him by the arms from a pear tree. The pear trees were then in bloom; the air was filled with their soft scent and the peasant’s screams. The rope that bound his arms passed over a branch and another townsman gripped it from below. When the rest of the group roared, “You’re not talking yet?” the rope would be pulled, the peasant’s feet would rise higher off the ground, and the ripping in his arms would grow more excruciating.

When he had been hoisted all the way up among the flowers, his sweat fell like rain and his face turned as pale as the pear-blossoms. While he writhed and pleaded, he shook the tree and released a gentle fragrance as petals fell to earth. I stared blankly at the tableau; to this day I cannot fathom the cruelty necessary to take a stranger, tie his hands behind his back, and hoist him by them into the air.

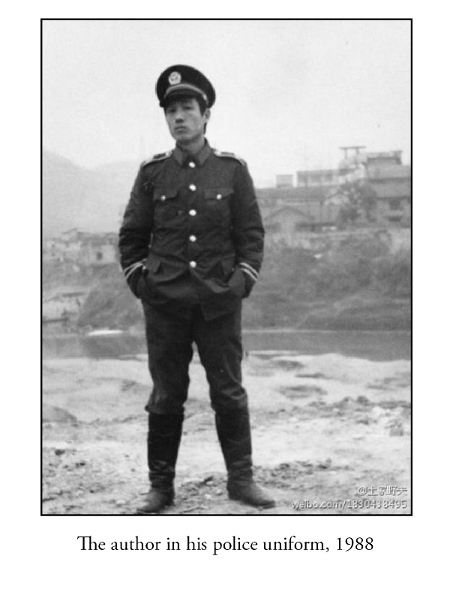

When I became a policeman, a veteran officer cheerfully explained to me that this kind of interrogation, in which the hands are tied behind the back and the prisoner is hung by them, usually should not be protracted beyond a half-hour. Any longer than that, and the suspect’s arms will be permanently crippled. I found his well-intentioned advice horrifying, and it brought back the memory of the scene I’d witnessed as a child; it occurred to me with a chill that this rule of thumb must have been distilled from many years’ worth of experiments.

But had this interrogation technique stopped being used? In a precinct house where I was assisting with a case in 1988, I was forced to witness a comparable scene. The Chief was quite experienced and, making use of heavy iron shackles, had placed the suspect in an awkward position named after a martial arts move. The two hands were shackled together behind the back, one reaching down with the elbow over the head while the other reached up from the waist. In this position the suspect was forced to kneel for a long time and the Chief left me to keep an eye on him. Being new to the profession, I was in no position to interfere and watched helplessly until the suspect passed out. Then I went to call the Chief to come take the heavy cuffs off him. The Chief exchanged the position of the two arms and continued the treatment.

I am by no means of a cruel temperament. How then could I witness a scene like this one and—though I felt some sympathy—act as though nothing was out of the ordinary? Later on, when I myself had become a convict, I thought a lot about this and realized that the training in cruelty which we’d received from our childhood had worn a callus on my soul. This unfeeling callus progressively hobbled our conscience and made us numb to human suffering. What’s more, our cowardice overwhelmed the little pity we could still feel, so we lacked the guts as well as the ability to change the system to which we’d grown habituated. When I heard the cries of a man being interrogated under torture, I didn’t dare put a stop to it, because I submitted to the uniform I wore. The uniform short-circuited my conscience; for a while I ascribed to it a supernatural power. Consequently when one day another man wearing that uniform struck me in the forehead with an electrified baton, there was nothing for me to say. Neither of us felt any personal animosity; it was only that his education led him to treat me as a foe.

Who, then, was the unseen Founder behind these countless acts of cruelty? Can we blame oppressive officials, those stock figures who have been passed down through the generations in a certain style of biographical history? Or is the toxin of this cruelty contained in the cultural traditions of our people?

The elementary education which my generation received had hatred as its starting-point. Teachers invented for us an unspeakably evil Old Society, and made everyone sing each day, with grief and indignation, the song:

In the Old Society, whips lashed my flesh,

And Mother could but weep.11

And now it was necessary for us to

Seize the whip and lash the foe.

This is how the violence and cruelty of youth were ignited, and the force thus released spread inevitably to the whole of society, polluting the manners and morals of that era down to the present day.

When the superintendent of a Detention and Transfer Center can incite the common people who’ve been locked up there to maltreat each other so badly that some of them die; when street-level Code Enforcers can wantonly chase down a peddler with their clubs, and go so far as to beat to death a bystander who photographs them; when soldiers can open fire on students and kill them without compunction, without any misgivings at all . . . could all these unconscionable acts of wickedness reflect the impact of education throughout society?

These days, I can find on the Internet a great many angry young men who rage against Japan and are itching to attack Taiwan. Rape them, kill them, nuke them, they roar against those who—in their minds—are enemies or traitors to China. It makes me very sad. These kids were untouched by the Cultural Revolution. They don’t even know about 1989. They didn’t receive the barbaric education we did. Whence came these cruel attitudes? If an evil administration were to take power, arising from and supported by people such as these youths, who knows what hideous crimes this country would inflict upon the world?

Clearly, some system that inculcates cruelty is still at work in our society; it has always been at work, spreading its influence unseen. The tension between oppressive officials and violent mobs grows ever worse, and the worst in human nature is brought to flower. For it is easy to cultivate hatred and cruelty among men; to propagate love, alas, is hard. When I consider the dreadful possibilities, I have a feeling that the peace of this night will prove fragile and short-lived. I can only guess what lies out there in the dark, but this vast city cocooned in insatiable self-indulgence makes me shudder with fear.